The UK, is home to two of the five European horseshoe bat species: the greater horseshoe (Rhinolophus ferrumequinum) and lesser horseshoe (Rhinolophus hipposideros). Both species behave in a somewhat stereotypical way, preferring to hibernate in caves and perching upside-down with their wings wrapped around the body, like a cocoon. However, in many ways they are unique. For example, the greater horseshoe is one of the largest UK bat species, weighing between 13 and 34g. Whereas the agile, plum-sized lesser horseshoe is one of the UK’s smallest bat species and will fly in a fast whirl of wings, reminiscent of a butterfly. They also tend to be long-lived creatures, with records of greater horseshoes over 30 years of age and lesser horseshoes over 20.

Unlike most bats, which contract their larynx and emit ultrasonic sounds through the mouth when echolocating, horseshoes emit their calls through modified nostrils, known as the nose-leaf, that amplifies the calls. This is made up of three parts, with the lowest part in the shape of a horseshoe, which is where the bat gets its name.

Habitat

Originally cave dwellers, horseshoe bats can now mainly be found using sun-warmed roof spaces as their summer breeding roost. They are, however, highly selective, preferring old stone buildings (usually pre-1900) that are relatively undisturbed. Hibernation still commonly takes place in caves, along with cellars and disused mines due to their stable cool temperatures.

Both species will fly out from their roosts and forage around hardwood woodlands and mature pastures. To reach these, they will follow linear features such as hedgerows and treelines. Unlike open fields and hills, these features provide a high insect density for foraging and are more protected from the wind and predation when the bats commute between foraging areas.

These linear features, and their adjacent field margins, can be managed under agri-environment schemes, and therefore implementation and management of these options may provide vital services to horseshoe bats in the local landscape. According to studies, landscape management is especially important within 2.5 km of roost sites, with bats rarely flying beyond this.

Foraging and diet

Like the pipistrelle, horseshoe bats are ‘aerial hawkers’, which means they capture insect prey in flight whilst constantly echolocating to pinpoint their prey. This often results in dramatic foraging scenes as they use their broad, round wings to capture airborne prey in tight manoeuvres. The heavier greater horseshoe will also have a favourite perch from which it can swoop in to capture airborne insects or take ground-dwellers such as spiders. The more agile lesser horseshoe will constantly circle a favourite area, flying less than five metres from the ground to startle small insects and then catch them in-flight. Larger prey is taken to a temporary night roost or is eaten as the bat hangs from a tree.

Commencement of foraging depends on light intensity. A higher light intensity will usually increase the amount of airborne insect activity (particularly of Diptera), and therefore foraging is mainly at dusk. Before dusk, horseshoe bats will partake in short light-intensity-checking flights and will not fly in heavy rain. Later during the night, the number of night-flying insects is relatively lower, so only the occasional forage flight from the roost site will occur. Differences in foraging time within the colony will depend on age (younger bats have poorer flight skills and so will emerge later than the adults), body reserves and temperature (lower energy levels and cooler temperatures during pregnancy will compel bats to forage earlier despite the higher predation risk from birds). Towards the end of the summer there is an increase in foraging activity as the bats try to increase fat reserves before hibernation, and with the increase of young taking wing.

Prey includes large insects such as chafer and dung beetles, noctuid moths, crane flies, caddis flies, midges, lacewings, beetles and some parasitic wasps.

Echolocation

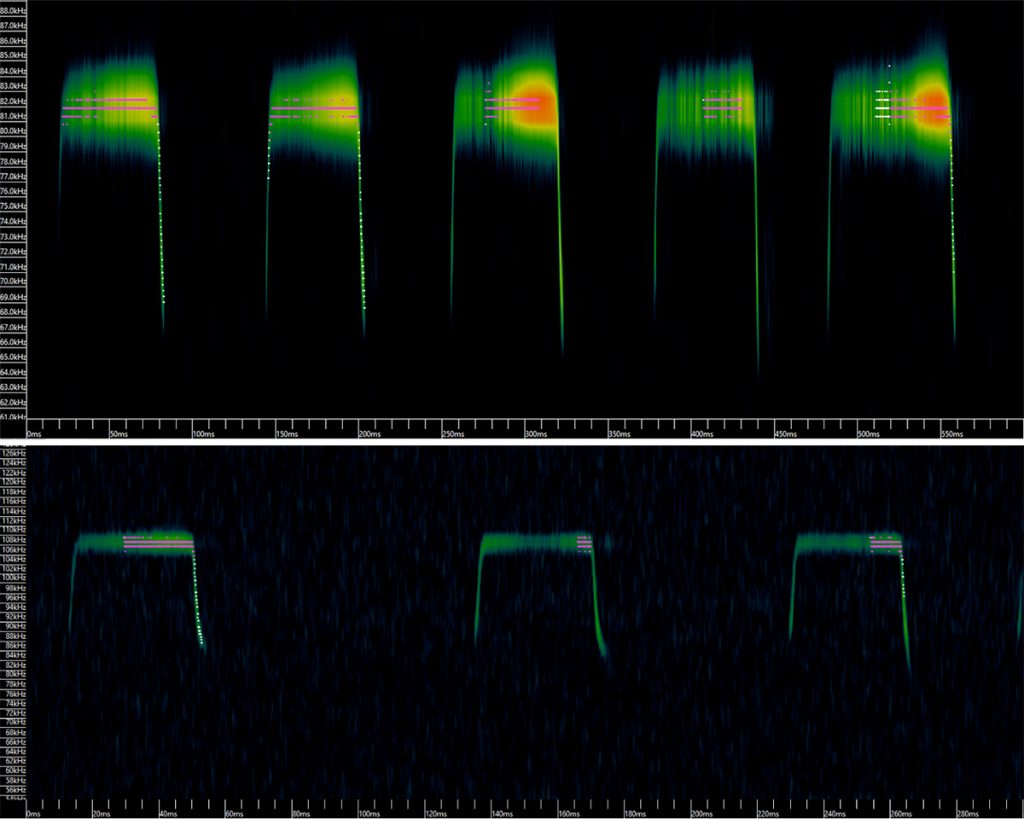

The greater horseshoe has a distinct call frequency from all other horseshoe species and therefore has a high identification confidence between 79-84kHz. The call of the lesser horseshoe bat is at a higher frequency at 106-116kHz and overlaps with Mediterranean and Mehely’s horseshoe bats, with these species having smaller ears to hear the higher frequency.

Distribution, protection and conservation

The distribution of British horseshoe bats is limited to southwest England and south Wales, and both species were categorised as near-threatened on the EU Red List in 2007. Over the last 100 years, a 90% decrease in the abundance of British greater horseshoe bats has been observed, and both species have been affected by changing land use and management, which have reduced the availability of nursery and winter roost sites.

The AgriBats team has been fortunate to record both species during our fieldwork and we hope that that our research can benefit them further through posing improvements to field margin management along linear features.

References

- Bontadina, F., Schofield, H., Naef-Daenzer, B., (2002). Radio-tracking reveals that lesser horseshoe bats (Rhinolophus hipposideros) forage in woodland. Journal of Zoology 258, 281-290.

- Duvergé, P., Jones, G., Rydell, J., Ransome R. D. (2000). Functional significance of emergence timing in bats. Ecography 23, 32-40.

- McAney, C. M., Fairley, J. S. (1988). Activity patterns of the lesser horsehose bat Rhinolophus hipposideros at summer roosts. Journal of Zoology 216, 325-338.

- McAney, C. M., Fairley, J. S. (1988). Habitat preference and overnight and seasonal variation in the foraging activity of lesser horseshoe bats. Acta Theriologica 33, 393-402.